From grassroots to global reverence, Gab Oliver retraces the rise, retreat and return of a label that shaped a scene…

By the mid-’90s, while peak-time anthems dominated global dancefloors, Melbourne started developing its own dialect—a darker, more hypnotic sound rooted in restraint. At its core was a small community of DJs and producers, united by a shared refusal to chase trends.

The sound they conjured was haunting: progressive but with a sparse architecture which created ample space for atmosphere. Indeed, a Zero Tolerance track spilled across the dancefloor with the tension of a coming storm. Uncompromising, yet cerebral.

(For a deep dive into the darker strain of progressive, head to our 2024 interview with McKeown & Bassiray.)

At the heart of this subterranean movement was Gab Oliver. As one of the founding forces behind Zero Tolerance Recordings, he helped shape a distinctly Australian strain that favoured dark groove over shiny gloss.

At the heart of this subterranean movement was Gab Oliver. As one of the founding forces behind Zero Tolerance Recordings, he helped shape a distinctly Australian strain that favoured dark groove over shiny gloss.

As Gab puts it: “Zero Tolerance to anything linear, one-dimensional, or—as I like to say—cheesy. Full stop.” It was a firm response to the filler flooding dancefloors at the time.

For six years, the label served as a vital nexus for the city’s underground – eventually spreading worldwide like sonic mycelium. In Melbourne, Oliver became the quiet cornerstone of the imprint and its emergent community. Beyond the city’s confines, you might know him better as Narcotik, Deep Funk Project, or Precision.

In this rare interview, Gab Oliver traces that journey which spans more than two decades—through humble beginnings, international resonance, and the quiet return of a sound that never truly left the shadows.

(And scroll to end of article to hear an exclusive Zero Tolerance mix compiled by Gab himself).

Steel Blades to Sound Waves

Gab Oliver’s entry into music came from far outside the club. At 15, he was working as an apprentice butcher in the Melbourne inner-suburb of Clifton Hill when he struck up a rapport with a regular named Pixie. One day, Gab mentioned a house party where he saw a DJ mix tracks across turntables for the first time.

“It blew me away,” he recalls. “I didn’t know what I was looking at, but I knew I wanted to do it.”

Gab was hooked. He found a secondhand DJ setup but had no idea what he was looking at. That’s when Pixie stepped in. No ordinary butcher-shop regular, Pixie was the former sound engineer for Aussie band Mi-Sex (remember “Computer Games”?). With his technical guidance, Gab spent $2,000 on a console, speakers, and two turntables. The path was set.

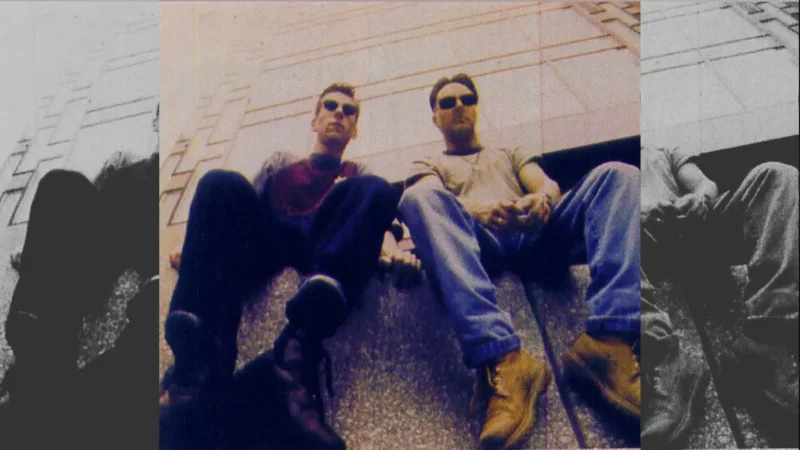

After early gigs at garage parties and church hall raves, Gab landed a three-night residency at Night Flight, a club on Melbourne’s outer edge. From there, he moved closer to the city’s heart, landing a pivotal stint at Gina’s on bustling Lygon Street—where he met Phil K (photo below).

The two became inseparable, bonding over records, gigs, and a shared obsession with sound. Gab’s next residency at Saint Elmo’s transformed the venue into a weekend ritual. It later expanded and rebranded as Heaven Nightclub—where, through Phil, he met Frank D, a DJ whose deep, acid-laced sound would profoundly reshape his musical instincts.

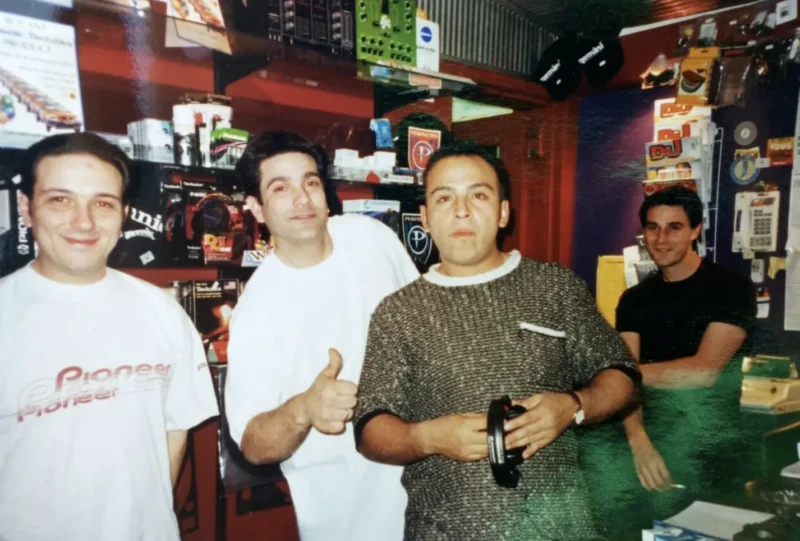

As Gab refined his sound behind the decks, his appetite for discovery grew. Regular record hunts with Phil and fellow digger Anthony Pappa eventually led him to Stewart Hanna, the English expat behind Melbourne’s iconic DMC Records. Their connection quickly deepened, and before long, Stewart invited Gab on a crate-digging pilgrimage across the UK.

“Those were some of the best weeks of my life,” Gab says. “I spent a fortune. We just dug nonstop.”

A Sonic Chemistry

Gab’s move into production began by chance. While DJing at Heaven Nightclub, he met the manager of R&B group Past to Present, who asked him to remix a track. With no studio experience, Gab was introduced to CJ Dolan. “It was my first taste of studio work, and I was hooked,” he says. The two hit it off.

In Australia’s rapidly evolving ’90s underground, CJ Dolan became a key figure. Alongside Sean Quinn, under the moniker Quench, he produced “Dreams”—a massive anthem that became an international hit.

By the early 2000s, it had surpassed a million in sales, its status as a classic all but assured.

Gab and CJ’s chemistry created emotionally austere tracks built for rooms rewarding patience. Sasha was an early supporter—a fact confirmed during a Melbourne gig where Gab, on warm-up duties, dropped “Chrome,” a track produced by him and CJ under their Chromium alias.

“It was about three-quarters through my set,” he remembers. “Sasha came straight into the booth to ask what it was.”

It was a validating moment—a sign they were onto something. “Chrome” carried all the hallmarks of their nascent sound. And it was beginning to resonate beyond their hometown.

Then came “Blue.”

The Blueprint

Gab and CJ had released music under many pseudonyms, but Narcotik fit their sound like a surgical glove. And with “Blue,” they made their most clinical cut.

Quintessential deep, dark, progressive—if the sound had a dictionary entry, ‘Blue‘ would be the track beside it. It was everything mainstream dance wasn’t: glacial, brooding, unapologetically restrained. A slow-motion spell simmering with tension, driven by a bassline running on pure sex.

At its core was a gentle whisper wrapped in jeopardy: Beware of every sound.

“That came from a session with a vocalist named Lisa,” Gab recalls. “We recorded a bunch of takes, but that one little section stood out. That’s all we used. It just worked.”

The whisper was loud enough to reach Sasha, who discovered the track via promo. What followed was quietly seismic: he licensed it as the opening track on Disc 2 of Global Underground: San Francisco, a mix still hailed by many as the gold standard of classic progressive house.

“Blue” opened doors. Platypus licensed the track after hearing it on Sasha’s mix, and this moody, minimal sound from Melbourne started finding favour on more discerning dancefloors. It was an explosion disguised as a slow burn. The impact, even to Gab, came as a quiet surprise.

In today’s low-attention social media paradigm, asking for that kind of patience feels radical. But that was the point and the ethos of Zero Tolerance.

“You can’t present our sound in six minutes. Sometimes it takes eight, nine, ten… and if it needs to go longer than that, then so be it. I don’t give a fuck.”

“Blue” represented the Zero Tolerance agenda: depth over dopamine, no compromises. It became the blueprint for everything that followed.

Born from Resistance

‘Fuck it—let’s start our own label’

While the global progressive wave leaned toward crowd-pleasing builds and melodic climaxes, Oliver’s circle was chasing something darker. That persistence birthed the label. As he recalls, it was a frustrating time if you were looking for something different.

It’s an energy infused into the Narcotik catalogue. Before cementing its legacy on Anthony Pappa’s NuBreed mix, their track ‘Conditions‘ drifted through a kind of no man’s land: too strange for the labels of the time.

Built on the same framework that made ‘Blue‘ so compelling, ‘Conditions‘ starts in the shadows: an ominous intro parading as an eerie wind whistling through the bones of abandoned house, a ghostly vocal hanging in the air before dissolving into saturated drums. This wasn’t trying to be big-room. It wasn’t trying to please. It was brooding, textural, and effortlessly cool: a track that made prog feel dangerous.

But it almost didn’t see the light of day.

Fuelled by belief in the sound… the conditions felt right. Hanna led from the front. “Stu put his balls on the line. He conceptualised it and made it happen.”

In the end, Zero Tolerance was born out of necessity, a response to a scene that started playing it safe. Founded by Gab Oliver, Stewart Hanna, and Phil K, it became a breeding ground for deep progressive experimentation that favoured subtlety over spectacle.

Cinema listening

A big part of the Zero Tolerance sound came from sampling. With limited access to vocalists, the team had to get resourceful, so they turned to cinema.

“We’d sit in the studio, put on a movie, and listen with intent,” Gab says. “We weren’t watching: we were hunting for sounds.”

The dialogue didn’t need to make sense, it just needed to feel right. During a viewing of the 90s cult vampire movie Blade : “There’s this scene with a vampire gangster, speaking gibberish at the table,” Gab recalls. “We heard it and just looked at each other, ‘That’s the one.’”

That spark became Digby & Oliver’s ‘Human‘.

That process that became a signature of the label’s sound: eerie snippets, half-heard voices, cinematic fragments that flickered in and out of the mix like the static-laced twitch of a failing radio feed.

They were crafting worlds using texture, tone, and tension as building materials.

It is Always Sunny in Melbourne

Local club night Sunny became the place where that energy transmogrified. If Zero Tolerance was the manifesto, Sunny was the altar where the heads came to worship. The now-legendary night became a playground for progressive’s darker edge. For Gab’s circle of DJs it was utopia.

“Sunny didn’t follow trends; it was about going deep, taking risks, and trusting the crowd to come along for the ride. You could go deep, dark, whatever you wanted, and they’d be there right with you.” It provided DJs a safe space to air unreleased tracks.

As Danny Bonnici recalled in our essential progressive breaks feature, it’s at Sunny where classic cuts like ‘Lydian & the Dinosaur’ growled into public consciousness and ‘Burma‘ received its wings.

The driving names behind the music were Ozzie L.A, who quietly helped shape this sound. (“He wasn’t loud or flashy, but his sets told a story.”) In the same vein, through sets simmering with restraint, Oliver became a vital thread in Sunny’s musical fabric. For reference listen to this 2002 mix.

And then there was Phil K.

Much has been written in tribute, but it bears repeating: his musical instinct bordered on the cosmic. In Melbourne it was gospel that Phil wasn’t ahead of the curve: he was the curve.

“He had this deep knowledge,” Gab reflects. “Like he could feel what was going to work before the crowd even knew what they wanted.‘ Phil’s thirst for new music was unquenchable. ‘He’d be on the phone all night, listening to promos nonstop. Anyone who knew him will tell you: he lived and breathed music.”

Back then, the legend of Phil K was already crystallising. “People would wait until 5AM just to hear his sets. That’s where he started introducing breaks, spinning our unreleased Zero Tolerance tracks before anyone else had even heard them. It was unreal.”

It was in those early hours—when the club was half-lit and the crowd fully locked in—that the sound truly took shape.

Progressive Breaks

At the time, Phil K and Andy Page (aka Hi-Fi Bugs) were deep in the breaks rabbit hole, pushing ideas that often outpaced the tech they had.

They were always two steps ahead of what was possible. Tracks like Lydian and the Dinosaur took days to edit. Sometimes they’d render for hours, only to scrap it and start again from scratch.

“That was the first progressive breaks track we put out on Zero Tolerance. It marked a magical period when that sound really started to form, especially through my work with KB (Kristo Beyrouthy aka Kaybee) as Precision.”

At the time, few others were making progressive breaks like they were. Tracks like Nightmare (Breaks Mix) and This Is How It Feels—both co-produced with KB—became part of the unofficial soundtrack to John Digweed’s Breaks Room at his monthly Bedrock event in London. In particular, then Bedrock resident Jonathan Lisle was an huge supporter.

“He really helped push that sound to a wider audience,” Gab remembers. “That era lined up with John launching Bedrock Breaks and Bedrock Black, which gave the style a bigger platform and serious credibility.” It’s remarkable to think that a sound born on the other side of the world could go on to influence the global scene.

“What’s wild is that the sound has lived on. It’s still influencing a new generation of producers like McKeown & Bassiray, who are now writing in that same vein. Labels are even asking them specifically for that progressive breaks sound, because it still stands apart from everything else coming out right now.”

Fade to Black—And Return

By 2005, progressive music had begun to shift; veering into colder, more electro territory. For Gab, the spark was fading. “I got married and focused on family. I still made music at home, but the label stopped. It needed to.”

Zero Tolerance released its final record in late 2004 and bowed out with quiet intention. The scene was shifting and rather than force it, he let it go.

“I wasn’t feeling it,” he says. “But I always knew I’d come back to it when it felt right again.”

Fifteen years later, in the chaotic stillness of the 2021 pandemic and lockdowns, the Zero Tolerance Bandcamp page lit up like a Christmas tree. Oliver revived the label, re-releasing the entire back catalogue. The irony wasn’t lost: Dark music, dark times. The catalyst? A reconnection with Stewart Hanna, and a new generation of kindred spirits in Darius Bassiray and Stuart McKeown.

“When I reconnected with Stu and Darius [McKeown & Bassiray], it just felt right,” Gab explains. “They’re from a younger generation, but they get it. They understand what this music is about.”

No Nostalgia, No Compromise

Since its return, Zero Tolerance hasn’t missed a beat. New releases landed from international names like EANP and Analog Jungs, while the all-Melbourne crew delivered work from Luke Chable, Danny Bonnici, Mike Rish, Jamie Stevens, and McKeown & Bassiray. It felt less like a comeback and more like a seamless continuation of the label’s ethos.

“The fundamentals are the same. Deep, drum-driven, hypnotic. It’s really not about nostalgia—more about evolution. The sound is modernised.”

Alongside the music, the crew launched No Nonsense, a new party series designed to spotlight the next generation of Zero Tolerance artists. True to its name, the night strips things back to the core. No gimmicks. No filler. No Nonsense. Just deep sets from artists who keep it real.

The events have already built a reputation for uncompromising programming and intimate energy, offering a space where the ZT philosophy can be experienced in real time.

“It’s about creative freedom,” Gab says. “That’s what we always stood for.”

After all these years, that still rings true: Zero Tolerance never played the game, and it still doesn’t. In a world chasing clicks and climax, it remains a sanctuary for the dark, slow burn.

And even if the world around them is changing, their mission will always stay the same.

THE FUTURE

A 4 track EP from Gab Oliver, a remix package of McKeown & Bassiray’s Behaved EP featuring Ricky Ryan & Futura City, and Kohra. An EP from Melbourne’s Michael Bennett plus more new music from Stuart & Darius, Diego Moriera, Wolftrax, and more in the pipe line.

2025 will also see the return of Deep Funk Project with Ivan Gough. We’re loving what Mike Isai’s doing too—his direction really speaks to us—as well as the deeper techno sound bubbling up right now.

But honestly, there’s no rigid schedule here. When the right records land, we’ll release them.

The music has to come correct.

*Every track is from Zero Tolerance’s post-2021 relaunch. No nostalgia, just fresh pressure.

Tracklist

1. Gab Oliver – Moody Intro {Unreleased}

2. McKeown & Bassiray – An Introduction {Zero Tolerance}

3. Gab Oliver – Drowning (Depth Institute Remix) {Zero Tolerance}

4. Gab Oliver – NFU {Unreleased}

5. Jamie Stevens – Path Of None (Analog Jungs Remix) {Zero Tolerance}

6. Luke Chable – Sealers Cove (Jamie Stevens Remix) {Zero Tolerance}

7. Hot TuneIK – Poema {Zero Tolerance}

8. McKeown & Bassiray – Cave (Dub) {Zero Tolerance}

9. DJ Bird – Slenderman {Zero Tolerance}

10. Kız Pattison – Weekend Existence (McKeown & Bassiray Remix) {Zero Tolerance}

11. Digby & Oliver – Human (Laura & Trevor Rose Remix) {Zero Tolerance}

12. Gab Oliver – Arcane {Zero Tolerance}

13. Jamie Stevens – The Black Ruby Of Voldesad {Zero Tolerance}

14. McKeown & Bassiray – Comet {Zero Tolerance}

15. Luke Chable & Ivan Gough – Disconnect {Zero Tolerance}

16. McKeown & Bassiray – Flat Surfaces {Zero Tolerance}

17. Wolftrax – Spacious {Zero Tolerance}

18. Gab Oliver – {Untitled Unreleased Track} {Unreleased}

19. DJ Bird – Darkside {Zero Tolerance}

20. Gab Oliver – Drowning (Danny Bonnici Remix) {Zero Tolerance}

21. Danny Bonnici – Electrical Disturbance {Zero Tolerance}